📈Compounders - Roll-Up

Acquisition-Driven Compounders - Introduction

In the vast universe of investment, certain business models, by their design and execution, become true value-generating machines over the long term. They don't depend on a single revolutionary product or a passing fad, but on a disciplined and repeatable system. Today, we're going to study one of the most powerful and often underestimated: the Acquisition-Driven Compounder model.

What is a Compounder?

At first glance, the concept is simple: these are companies whose core strategy consists of growing through the systematic and programmed acquisition of other, generally smaller, private, and niche companies.

However, this definition falls short. What truly distinguishes them is not just buying other companies, but how they do it and what they do afterward. Unlike the megamergers that dominate economic headlines, these companies don't look for a single "transformative acquisition." Their approach is more like that of a patient gardener than a trophy hunter. They make multiple small, tactical acquisitions each year, integrating them into an ecosystem that continuously enhances their value.

The key characteristics that define these champions of value creation are:

-

Strong free cash flow generation: They are inherently profitable businesses that produce more cash than they need for daily operations.

-

Exceptional capital allocation skills: Their main talent is reinvesting that surplus cash flow into buying good businesses at attractive valuations.

-

Decentralized business models: They allow acquired companies to maintain their autonomy, culture, and entrepreneurial spirit.

-

Dual growth engine: They grow both through acquisitions (inorganic) and through the improvement and development of the businesses they already own (organic).

Studying this business model offers us a unique perspective, halfway between public market investing and private equity, but with the advantages of liquidity and an infinite time horizon.

🏛️Three Fundamental Pillars

The extraordinary and sustained performance of these companies is not a matter of chance. It is built on three interconnected pillars that form the core of their philosophy and strategy.

1. Capital Allocation

This is, without a doubt, the most important pillar. The management of these companies thinks and acts like investors, not just managers. Their main function is not to optimize the day-to-day operations of each of their subsidiaries, but to decide where and how to reinvest the capital generated by the group as a whole to maximize long-term shareholder value.

-

Sources of Capital: The main source is the free cash flow generated by their operations. They systematically avoid excessive use of capital increases (issuing new shares) so as not to dilute existing shareholders. The use of debt is prudent and is kept at conservative levels (generally below 2.5 times EBITDA) to be able to act flexibly even in times of crisis.

-

Use of Capital: The priority destination for capital is the acquisition of small and medium-sized private companies. They look for niche businesses, often family-owned, with a proven track record of profitability and that, due to their size or sector, have limited reinvestment opportunities on their own. By offering them a "permanent home," the Compounder can redirect the cash flow from these companies to new acquisitions, creating a virtuous circle of growth.

2. Decentralization

Here lies the operational magic of the model. Instead of seeking forced synergies and fully integrating acquired companies into a rigid, centralized corporate structure, the best Compounders opt for autonomy.

The central idea is that important decisions about customers, suppliers, and day-to-day operations should be made as close to the market as possible. The management team of the acquired company knows its business best. Imposing a centralized bureaucracy from corporate headquarters often destroys what made that company valuable in the first place: its entrepreneurial culture.

The book "Billion Dollar Lessons" uses a brilliant metaphor to describe the failure of many centralized acquisition strategies: it's like "buying a bunch of rock bands to form an orchestra." On paper, it seems logical to think about cost and sales synergies, but in practice, forcing different cultures and personalities to work in the same way rarely works. It ends up destroying creativity and agility.

Successful Compounders, in contrast:

-

Keep corporate headquarters extremely lean (lean HQs).

-

Allow subsidiaries to operate with their own profit and loss (P&L) statements.

-

Encourage autonomy and responsibility in decision-making.

Synergies are welcome if they arise naturally and voluntarily between "sister companies," but they are never imposed from above.

3. People and Culture

Capital and structure are nothing without the right people. These businesses are focused on people.

-

Owner-Operator Mindset: They seek to acquire companies where the founders or management team want to stay and continue to manage their "baby." They are often incentivized by allowing them to maintain a minority stake or through bonuses tied to long-term profitability.

-

High Insider Ownership: It is very common for the management of the Compounder and its subsidiaries to be significant shareholders. This aligns their interests with those of external shareholders. As the saying goes, "no one washes a rental car with the same care as their own."

-

"Permanent Home" Culture: Unlike private equity, which typically has a 5-7 year investment horizon before selling the company, Compounders offer a definitive home. This very long-term perspective is a powerful draw for family business owners who care about their company's legacy and the future of their employees. They become the "preferred buyer" not by offering the highest price, but by offering the best cultural and strategic continuity.

🎯Acquisition Strategies: Specialists vs. Generalists

Within the universe of Compounders, we can distinguish two main archetypes based on their acquisition approach:

1. Specialists

These are companies that focus on acquiring businesses within a single sector or market vertical. For example, a company that only buys and integrates HVAC installation companies or software companies for a specific legal niche.

-

Advantages: They can develop a very deep knowledge of the sector, which allows them to better identify good opportunities and share best practices more effectively.

-

Risks:

-

Limited Growth Runway: The universe of companies they can buy is finite. Once they dominate their niche, growth slows down.

-

Risk of Failed "Roll-up": The temptation to centralize to extract synergies is much greater in a single vertical. This can lead to the failures described above if the entrepreneurial culture is destroyed.

-

Cyclical Vulnerability: By being concentrated in a single sector, they are more vulnerable to crises or technological changes that affect that industry.

-

Among specialists, the most successful models are those that operate in global, large, and fragmented markets, and that, despite their specialization, maintain a high degree of decentralization.

2. Generalists

These companies are sector-agnostic. They acquire good businesses in multiple verticals, often with no apparent relationship between them. One day they might buy a demolition equipment manufacturer and the next a dental product distributor.

-

Advantages:

-

Almost Infinite Growth Runway: Their acquisition universe is the set of all small and medium-sized profitable companies, which gives them much greater growth durability.

-

Diversification: The risk is much more diversified. A crisis in one sector has a limited impact on the group as a whole.

-

Flexibility: They can pivot their acquisition focus towards the sectors that offer the best opportunities at any given time.

-

-

Risks: The main criticism is the apparent lack of synergies. However, as we have seen, the best Compounders do not force synergies. Their competitive advantage does not lie in operational combination, but in excellence in capital allocation and in creating a high-performance culture.

In practice, many generalists end up developing "mini-specializations" or clusters of expertise as they acquire several companies in the same field, combining the best of both worlds.

🚀Dual Growth Engine: Acquisitions and Organic Growth

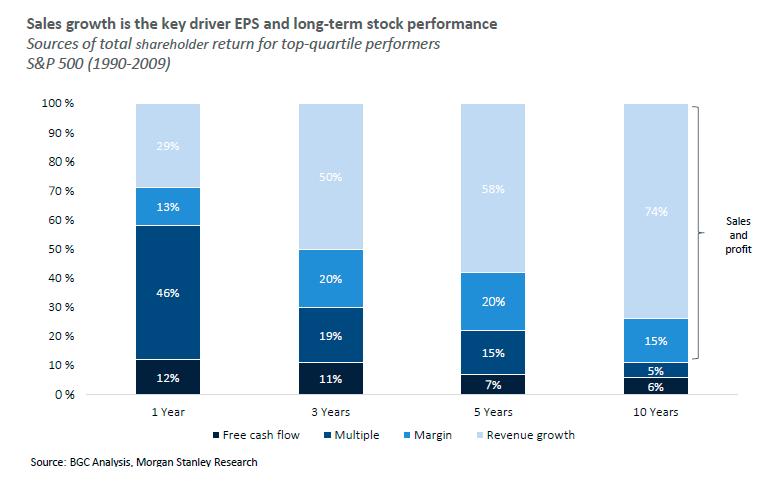

The growth in earnings per share (EPS) of these companies, which is the main driver of long-term stock value, comes from two complementary sources.

1. Growth by Acquisition (M&A)

This is the main and most visible engine. Their process is a well-oiled organizational capability, not a sporadic event.

-

Structured Process: They have internal teams dedicated to searching, analyzing, and executing acquisitions.

-

Programmatic Approach: They carry out many small deals per year. This reduces the risk of each individual acquisition and creates an "averaging" effect that smooths out results.

-

Valuation Discipline: By avoiding competitive auction processes and being the "preferred buyer," they manage to acquire companies at very attractive valuation multiples (often between 5 and 8 times EBIT), well below what is paid in public markets.

2. Organic Growth

This is the often-ignored engine, but it demonstrates the quality of the model. Organic growth is proof that the acquired companies not only survive but thrive and develop under the new umbrella.

How do they achieve this?

-

Injection of Energy and Structure: Acquired companies are often in a phase of succession or stagnation. The Compounder's entry provides new energy, professionalizes certain areas (without falling into bureaucracy), and injects ambition.

-

Best Practices: They encourage the exchange of knowledge between group companies in areas such as pricing (moving from "cost plus margin" to "value-based pricing"), working capital management, or international expansion.

-

Access to Capital: Subsidiaries have access to the group's capital to finance their own organic growth, something that would be more difficult for them as independent companies.

Healthy and sustained organic growth is the definitive sign that the Compounder is not a mere "financial engineer," but a true business builder.

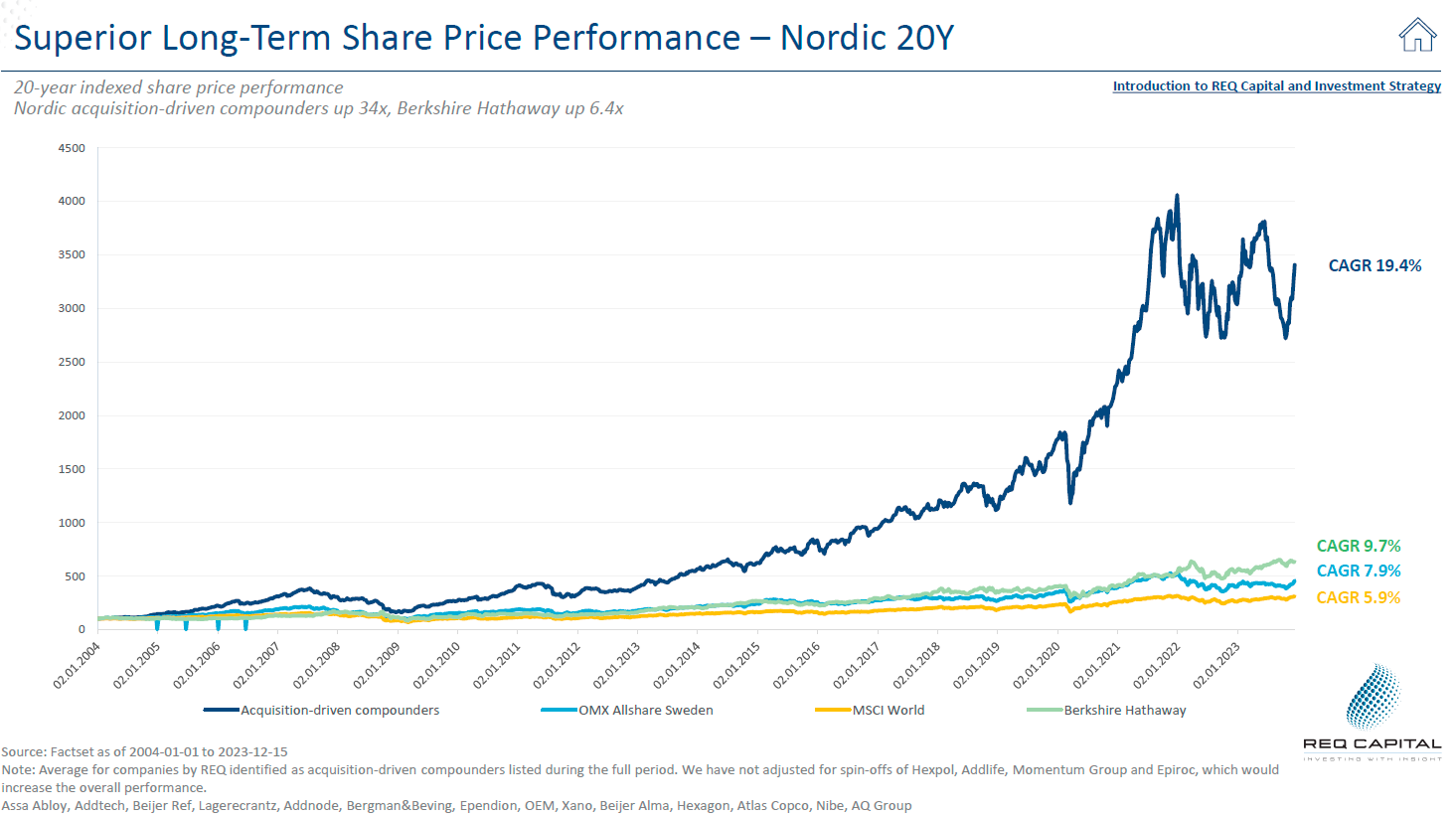

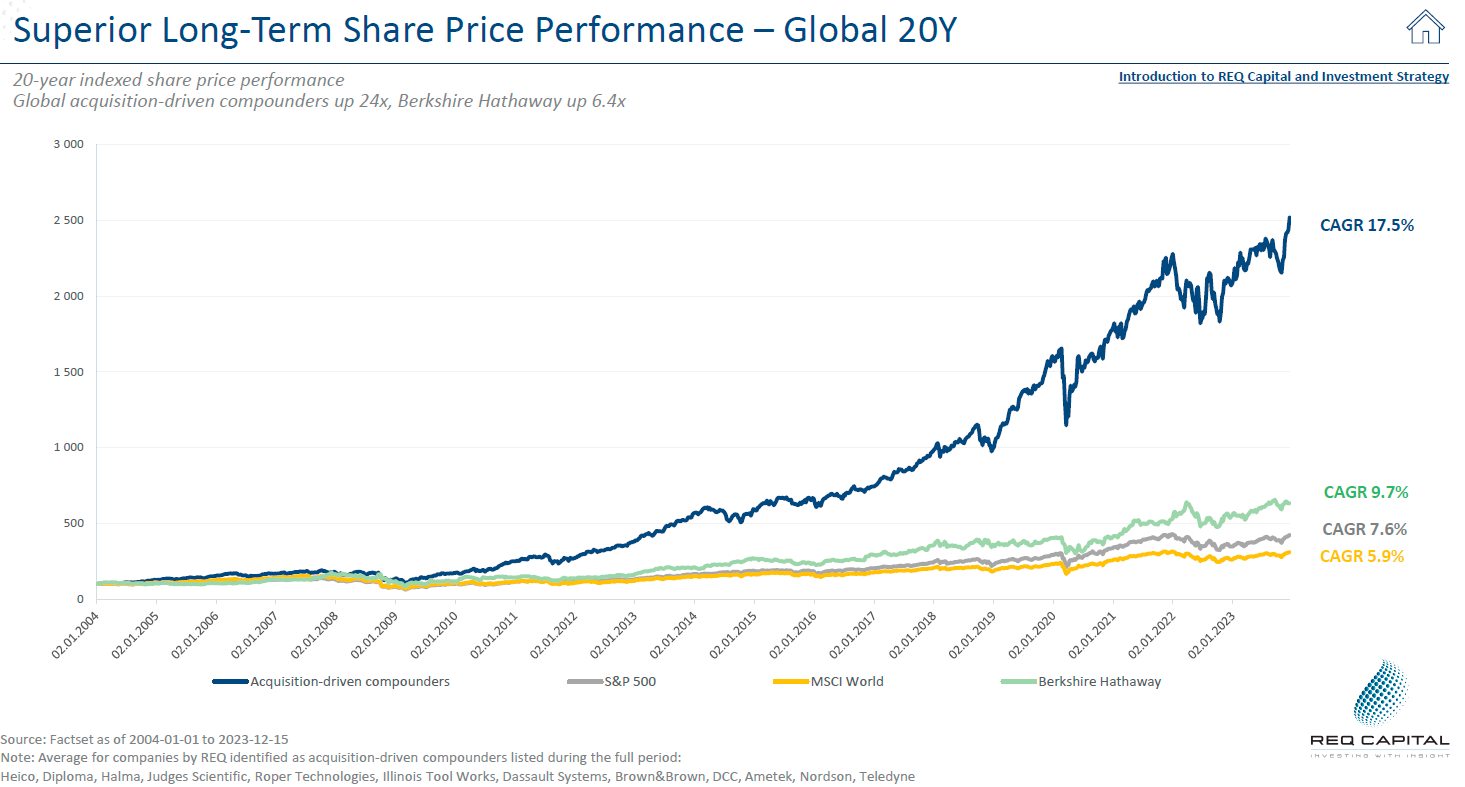

📊Superior Long-Term Performance: The Empirical Evidence

The theoretical appeal of this model is confirmed by spectacular historical performance. Various studies and market data analyses show that, as a group, high-quality Compounders have systematically and by a wide margin outperformed the main stock indices and other investment archetypes.

For example, an analysis of Nordic Compounders over a 20-year period (from 2004 to 2023) showed that their value multiplied by 34, while an investment giant like Berkshire Hathaway multiplied by 6.4 and the MSCI World index by a much smaller factor. Over a 10-year period, global Compounders multiplied their value by 5, compared to Berkshire's 3 times.

This superior profitability is not due to a single lucky year, but to the consistency of the model. Their ability to continuously reinvest capital at high rates of return (above 15-20%) for decades is the mathematical formula of compound interest applied to the business world.

🚩Risks and Red Flags to Watch Out For

Although the model is powerful, it is not without risks, and not all companies that claim to be Compounders execute it successfully. As investors, we must be alert to certain warning signs:

-

Change in M&A Strategy: A company that historically made small acquisitions and suddenly announces a large, "transformative" purchase. This often means paying a much higher multiple and carries an enormous integration risk.

-

Excessive Use of Shares to Pay: The best Compounders pay with the cash flow they generate. The recurring use of new shares to finance purchases is a sign that the business does not generate enough cash and also dilutes existing shareholders' value.

-

Increased Indebtedness: Leverage that consistently exceeds 2.5-3.0 times EBITDA is a red flag. It reduces flexibility and increases the company's fragility in a recession.

-

"Synergies" Talk: When the justification for a purchase is based mainly on the "cost and sales synergies" that will be achieved, one must be skeptical. These synergies often never materialize and are an excuse for overpaying.

-

Centralization: Efforts to unify brands, IT systems, or sales teams at the group level. This is the first step towards destroying autonomy and entrepreneurial culture.

-

High Turnover of Subsidiary Managers: If the CEOs of the acquired companies leave the group shortly after the purchase, it is a sign that the "permanent home" culture is not real.

-

Opaque Communication: Lack of transparency about the multiples paid in acquisitions or the organic performance of the companies.

* Most of the information contained here has been extracted from the following report on Nordic Compounder Companies. This philosophy of growth and value creation is widespread in this geography. Below are some examples of companies in the sector. *

Link to Nordic Compounders Report

Examples of Nordic Companies

Generalists:

-

Addtech

-

Atlas Copco

-

Indutrade

-

Lagercrantz

-

Lifco

-

Vitec

-

Volati

Specialists:

-

Bravida

-

Beijer Ref

-

Hexatronic

-

Nibe

-

Sweco

Examples of Global Companies

Generalists:

-

Constellation Software

-

Danaher

-

DCC

-

Diploma

-

Halma

-

Judges Scientific

-

Roper Technologies

Specialists:

-

Brown & Brown

-

Heico Corporation

-

LVMH

-

Thermo Fisher

-

Watsco