The evolution or involution of stocks

In the dynamic world of stock investing, the perceived value of a company is constantly changing. Throughout the life cycle of a successful stock, it goes through multiple phases of valuation and market perception: from being considered a "deep value stock" to becoming a "growth stock." This transformation reflects the evolution of the underlying business and how investors interpret its prospects over time.

The purpose of this guide is to offer a detailed perspective on how great companies transition through different valuation paradigms and how investors can leverage these phases to design profitable strategies.

1. The Life Cycle of Winning Stocks

Almost all major market winners were, at some point, undervalued stocks. Throughout their stock market journey, these companies have been considered cheap, expensive, loved, and hated, depending on the economic cycle and market perception.

Companies change, so does the market

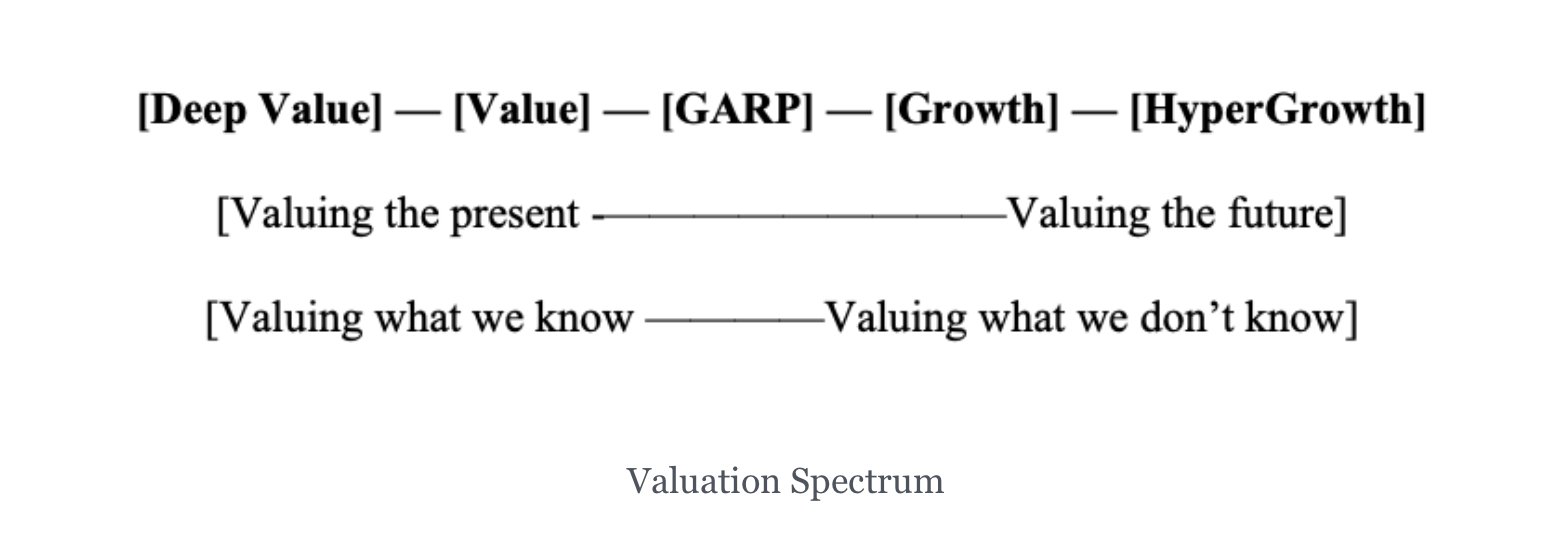

Companies are in constant evolution, which shifts the narrative and market expectations around them. Therefore, successful stocks do not maintain a single investment profile; they go through several archetypes:

- Deep Value

- Value

- GARP (Growth At a Reasonable Price)

- Growth

Classic example: Microsoft

- In 1999, it traded at a Price/Earnings (P/E) ratio of 80, fueled by investor euphoria around growth stocks.

- In 2009, its P/E dropped to 9, attracting deep value investors.

- In 2016, it returned to a P/E of 40, drawing interest again from growth investors.

Holding a stock through this entire cycle is a feat that very few investors achieve. Even iconic figures like Bill Gates have been among the few to maintain such long-term positions.

Walmart

Historically, Walmart has traded within a range of 10 to 60 times its earnings, attracting both value and growth investors. This demonstrates how valuation multiples can oscillate even in high-quality companies.

2. The Valuation Dilemma

The challenge of valuation

Valuation is a subjective concept, as each investor prioritizes different aspects and methodologies. This is a field where multiple approaches coexist, and there is no single "correct" answer.

Segmenting investors by valuation

Investors typically specialize or fall into one or two "camps" of valuation. These are:

| Type of Investor | Main Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Deep Value | Seek companies trading below their obvious intrinsic value. |

| Value | Focus on companies with a good price/earnings ratio and solid fundamentals. |

| GARP | Combine value criteria with reasonable growth prospects. |

| Growth | Prioritize companies with great future expansion potential, even at high multiples. |

Stock transfers between investors

In practice, winning stocks are transferred from one type of investor to another as their valuation perception changes:

- A deep value investor sells to a value investor.

- The value investor passes it on to a GARP investor.

- The GARP investor eventually sells to a growth investor.

And the reverse process happens with losing stocks.

3. Duration vs. Specialization

📌 Relationship between specialization and time horizon

The more specialized and rigid an investor is in their valuation criteria, the shorter their investment horizon tends to be. This is because they aim to capture returns in clear and time-limited windows of opportunity.

📌High turnover as a strategy

The best deep value investors tend to have high turnover rates, as they find opportunities that allow them to quickly generate returns and replace sold positions with new high-expected-return opportunities.

📌 Buffett’s transition

As his assets under management grew, Buffett migrated towards the right side of the spectrum, integrating growth criteria into his methodology. However, even at this stage, he remains true to his essence of seeking undervalued companies.

4. The Challenge of Big Winners

📌 The phenomenon of “multibaggers”

Despite being the goal of many investors, only 4% of the stocks Buffett has purchased throughout his career have remained in his portfolio for over 10 years. The rest have been sold.

📌 The difficulty of holding “monster winners”

Holding long-term positions in companies that become “multibaggers” is complex, as they are constantly evolving and may change their risk profile, expected returns, and valuation.

📌 Example of AutoZone

Companies like AutoZone, which have maintained a stable valuation range (between 13 and 20 times earnings) during much of their upward trajectory, are an exception and make the task of “holding” positions easier.

5. The Art of Adapting

📌 There is no single path

Each investor develops their own style. Some achieve excellent results by sticking to their niche, while others broaden their valuation range to hold positions for longer.

📌Reasons to expand the time horizon

- Difficulty in quickly finding new high-return opportunities.

- The need to manage larger portfolios (AUM) without compromising the strategy.

- Avoiding the exhaustion that a high-turnover approach can cause, as happened to Peter Lynch.

📌Final reflection

Great stocks change and evolve. The key is for the investor to decide whether to remain rigid and specialized or to adapt and evolve alongside the markets.