Balance

Introduction to the Balance Sheet

The balance sheet, also known as the statement of financial position, is one of the three main financial statements used to assess a company's financial health.

Its purpose is to provide a clear and detailed snapshot of an organization’s economic situation at a specific point in time. This report reflects what the company owns (assets), what it owes (liabilities), and the owners' equity (equity or shareholders' capital).

Time Frame of the Balance Sheet

Unlike other financial statements such as the income statement, which covers a specific period (monthly, quarterly, or annually), the balance sheet represents a snapshot at a given moment. In other words, it shows the company’s financial position as of a specific date, such as December 31.

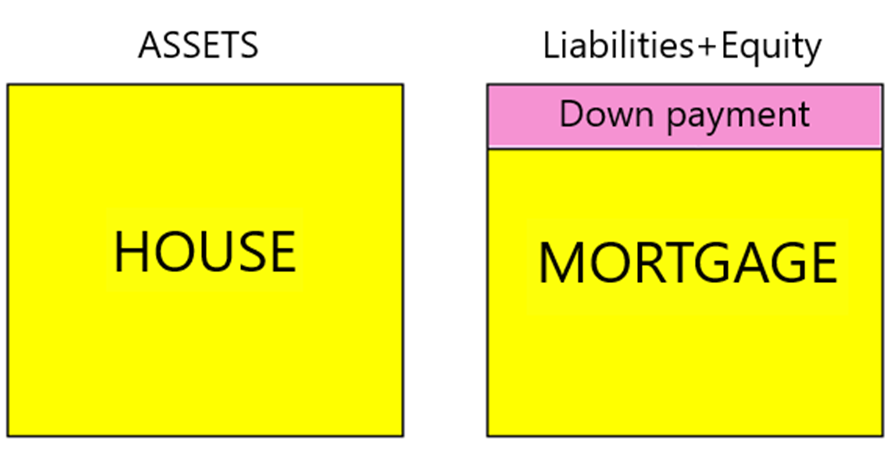

Relation to Personal Life

In personal life, the balance sheet resembles a summary of your personal finances: it includes what you own (assets like bank accounts, investments, or properties), what you owe (mortgages, loans, or credit card debts), and your net worth. This information is essential for making informed decisions about spending, investments, and savings.

Structure of the Balance Sheet

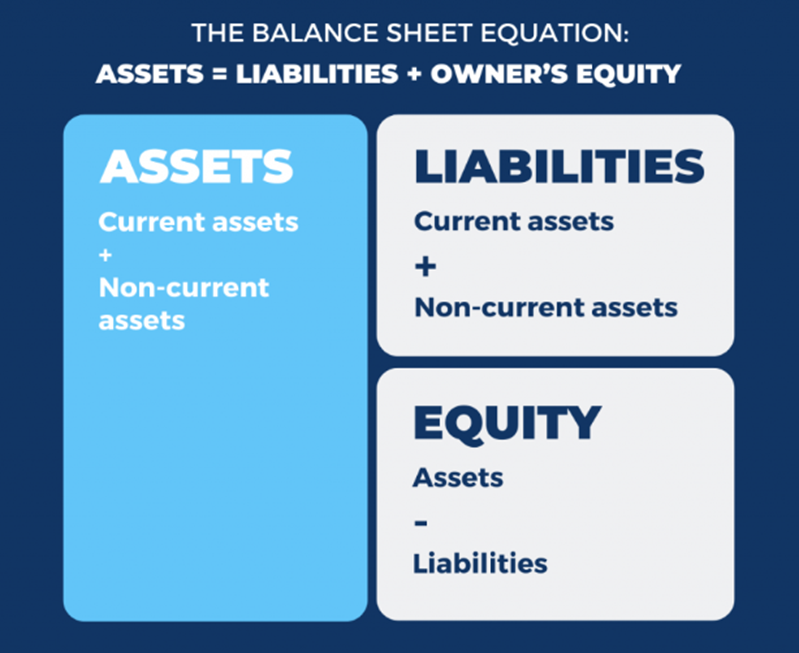

The balance sheet is divided into three main sections:

1. Assets (Investments)

2. Liabilities (Debt)

3. Equity (Shareholders’ Equity or Owner’s Capital)

*The Balance Sheet is Organized from Top to Bottom. At the top are the most liquid assets/liabilities, descending to less liquid assets/liabilities.

1. Assets

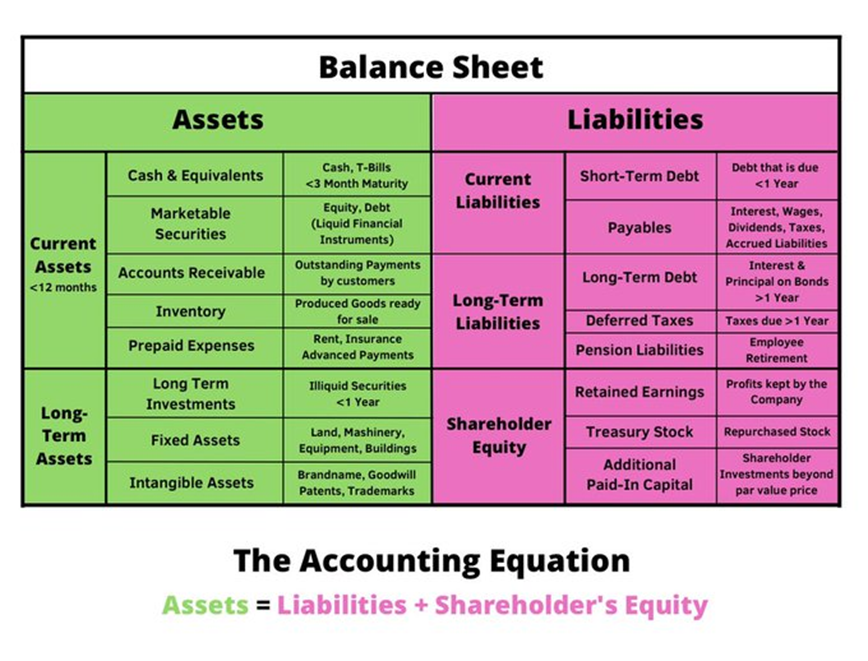

Assets represent all the resources a company owns or controls that have future economic value. These are divided into two main categories:

1.1 Current Assets (Short-Term)

These are assets expected to be converted into cash or consumed within one year or less. Key examples include:

· Cash and Equivalents: This includes cash on hand, bank accounts, and other highly liquid instruments like Treasury bills with maturities of less than three months.

· Short-Term Investments: These consist of instruments like stocks and bonds that can be liquidated within one year.

· Accounts Receivable: Represents the money owed to the company by its customers. An excessive increase in these accounts can be a red flag, indicating collection issues or an overly lenient credit policy.

· Inventory: Includes raw materials, work-in-progress items, and finished goods ready for sale.

· Other Current Assets: May include prepaid expenses such as rent or insurance.

1.2 Non-Current Assets (Long-Term)

These are assets that the company does not expect to convert into cash within the next year. Common examples include:

· Long-Term Investments: Financial assets such as stocks or bonds that the company plans to hold for more than a year.

· Tangible Assets: These depreciate, have a finite life, and are acquired or constructed. Their value is determined by market conditions and accounting standards.

o Properties, plant, and equipment, such as land, buildings, machinery, and vehicles.

o Biological Assets: Living animals or plants related to agricultural activities.

· Intangible Assets: These amortize, may have an indefinite life, and are created through intellectual or legal effort. Their value is determined by comparison with similar assets or estimated future income.

o Brands, franchises, customer portfolios, patents, software, licenses, copyrights, etc.

· Goodwill and Badwill: Goodwill arises when a company acquires another for a price exceeding the fair value of its net assets. Badwill indicates a purchase below this fair value. Both concepts must be adjusted for impairment when necessary.

2. Liabilities

Liabilities represent a company’s obligations to third parties. These are also classified as current and non-current.

2.1 Current Liabilities (Short-Term)

These are obligations the company must settle within one year. Examples include:

· Accounts Payable: Debts for goods or services purchased to operate the business.

· Customer Advances: Payments received for goods or services not yet delivered.

· Short-Term Bank Loans: Financing with a maturity of less than one year.

· Dividends Payable: Commitments to shareholders for profit distribution.

· Taxes Payable: Accrued tax obligations.

2.2 Non-Current Liabilities (Long-Term)

These are obligations the company must settle over a period longer than one year. Examples include:

· Long-Term Notes Payable: Obligations formalized through contracts.

· Long-Term Bank Loans: Credits typically used for investments in fixed assets.

· Bonds or Debentures: Debts issued as negotiable securities.

3. Equity (Shareholders’ Equity or Owner’s Capital)

Equity represents the residual resources belonging to shareholders after deducting liabilities from total assets. Its components include:

· Preferred Shares: Have priority in dividend payments and asset liquidation.

· Common Shares: Represent basic ownership in the company and provide voting rights.

· Retained Earnings: Accumulated profits not distributed as dividends.

· Treasury Shares: Shares repurchased by the company that have not been reissued.

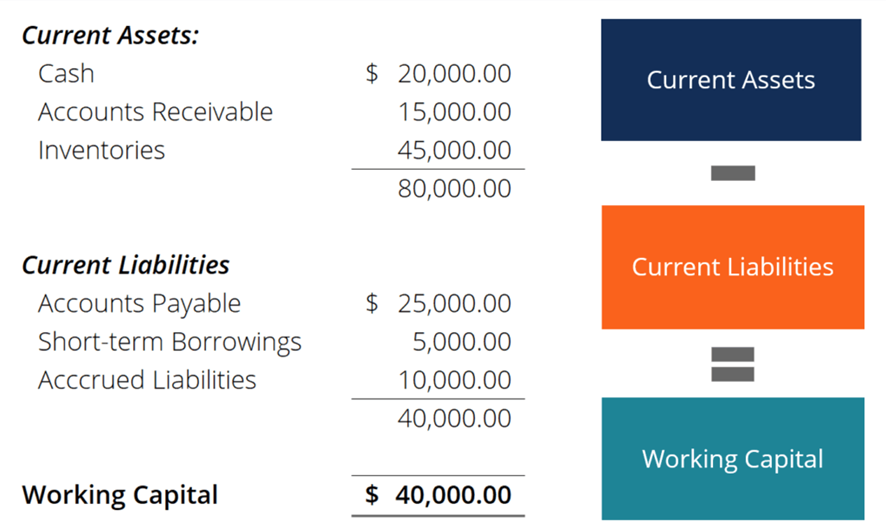

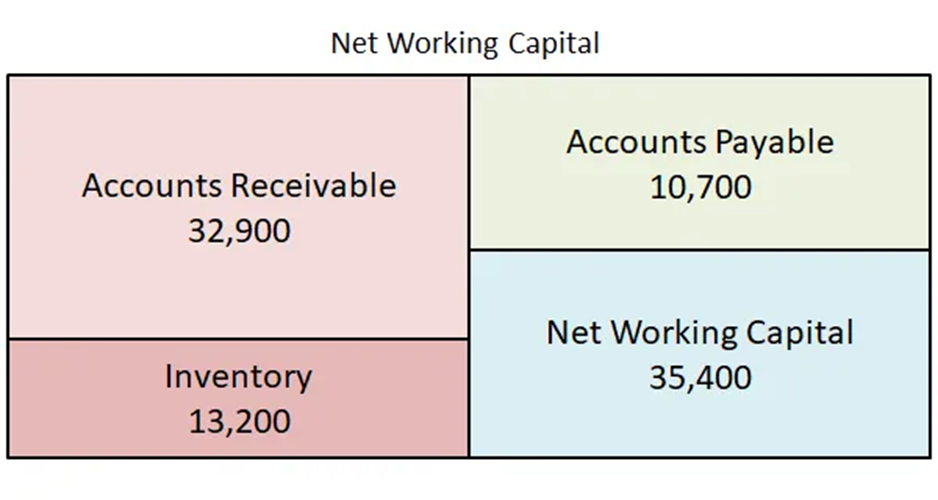

4. Working Capital

Working capital, also known as circulating capital or simply "WC," is a fundamental metric in financial analysis for businesses. Its importance lies in its ability to reflect a company’s capacity to manage liquidity and finance short-term operations.

Example: If a company has $50,000 in current assets and $30,000 in current liabilities, its working capital is $20,000. This indicates that it has sufficient liquidity to cover its short-term obligations.

Operational Definition of Working Capital

While traditionally defined as the difference between current assets and current liabilities, its operational interpretation provides a more practical view for analyzing cash generation and business management. This approach excludes financial elements and cash, focusing on accounts directly related to business operations:

· Current Operating Assets:

o Inventory.

o Trade receivables (customers).

o Prepaid expenses.

· Current Operating Liabilities:

o Trade payables (suppliers).

o Unpaid wages.

o Customer advances.

o Factoring.

4.1 Investment in Working Capital

4.1.1 Positive Working Capital

Investing in working capital involves advancing funds to finance operations before generating revenue. This is common in project-based or manufacturing companies (positive working capital).

Examples:

Ø Construction Company: A construction company tasked with building a bridge must purchase materials, hire personnel, and rent machinery before receiving partial payments from the client.

Ø Technology Consulting Firm: In a software development project, a company must pay salaries and tools before reaching revenue-generating milestones.

Ø Winery: A winery invests in wages, supplies, and operating costs during the years required to mature its wines, without immediate revenue.

4.1.2 Negative Working Capital

In certain industries, such as supermarkets and airlines, operating with negative working capital is common and advantageous. This occurs when current operating liabilities exceed current operating assets.

Examples:

Ø Supermarkets: They purchase inventory on credit (30, 60, or 90 days) but sell it for cash (immediately).

Ø Airlines: They receive payments in advance for future flights, while operating costs are incurred later.

Negative working capital allows these companies to finance operations with payments received before incurring expenses.

4.2 Divestment in Working Capital

Divestment occurs when working capital is reduced, generating short-term liquidity. This is common in companies facing declining sales.Example:

A manufacturing company reduces inventory purchases in response to lower orders, temporarily improving cash flow.

4.3 Key Ratios

4.3.1 Inventory Turnover

· Measures how many times a company sells and replenishes its inventory within a specific period.

· DIH (Days Inventory Held): Reflects the number of days inventory remains in storage or the time it takes to convert inventory into sales.

o Formula: DIH = Average Inventory / Daily Cost of Goods Sold

§ Where:

§ Average Inventory = (Beginning Inventory + Ending Inventory)

§ Daily Cost of Goods Sold = Annual Cost of Goods Sold / 365

· A low DIH indicates efficient inventory management.

· A high DIH may indicate excess inventory, leading to higher costs or obsolete products.

4.3.2 Accounts Receivable Turnover

· Measures how often a company collects payments from its customers within a period.

· DSO (Days Sales Outstanding): Indicates the number of days it takes the company to collect receivables after a sale.

o Formula: DSO = Average Accounts Receivable / Daily Credit Sales

§ Where: Daily Credit Sales = Annual Credit Sales / 365

· A low DSO shows customers pay quickly, improving cash flow.

· A high DSO may signal collection issues or overly lenient credit terms.

4.3.3 Accounts Payable Turnover

· Assesses how long a company takes to pay its suppliers.

· DPO (Days Payable Outstanding): Represents the number of days the company takes to settle accounts payable.

o Formula: DPO = Average Accounts Payable / Daily Cost of Goods Sold

§ Where: Daily Cost of Goods Sold = Annual Cost of Goods Sold / 365

· A high DPO indicates effective use of supplier credit.

· An excessively high DPO may cause tension with suppliers or loss of early payment discounts.

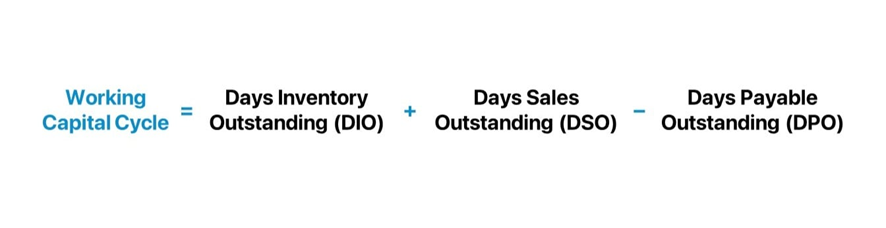

4.4 Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC)

The three indicators above form part of the cash conversion cycle:

Cash Conversion Cycle = DIH + DSO − DPO

A shorter cycle is generally preferable as it indicates that the company converts its operating assets into cash more quickly, reducing the need for external financing.

4.5 Impact of Working Capital (WC) on the Cash Flow Statement

Adjustments for changes in WC reflect the discrepancy between actual inflows and outflows.

Examples:

· Increase in Inventory: Reduces cash flow as funds are tied up in unsold goods.

· Increase in Receivables: Indicates unpaid sales, reducing cash inflow.

· Increase in Payables: Generates cash inflow by deferring payments to suppliers.

4.6 Factoring and Its Relationship with WC

Factoring is a financial tool that allows a company to obtain immediate liquidity by assigning its accounts receivable (invoices) to a financial institution or specialized company, known as the factor. It is particularly useful for companies needing to accelerate cash flow without waiting for customers to pay their debts within agreed terms.

4.6.1 Key Characteristics of Factoring:

- Invoice Assignment: The company transfers outstanding invoices to the factor.

- Immediate Liquidity: The factor pays the company a percentage of the invoice value (typically 80%–90%) upfront.

- Collection Management: In some cases, the factor handles the collection process from the customers.

- Non-Payment Risk:

-

- Non-Recourse Factoring: The factor assumes the risk if the customer fails to pay.

- Recourse Factoring: The company remains liable if the customer defaults.

-

4.6.2 Advantages of Factoring:

· Improved Cash Flow: Converts credit sales into readily available cash.

· Outsourced Collection: Reduces administrative effort related to tracking accounts receivable.

· Risk Reduction: Non-recourse factoring protects the company from non-payment risks.

· Ease of Planning: With more liquidity, it becomes easier to plan investments or cover operational needs.

4.6.3 Disadvantages of Factoring:

· Costs: Includes commissions and interest, which can be high depending on invoice volume and risk.

· Loss of Control: Relationships with customers may be affected if the factor is overly aggressive in collections.

· Limitations: Not all invoices are accepted; the factor evaluates the risk associated with the company’s clients.

Factoring is commonly used by companies with long collection cycles or those seeking to avoid liquidity issues while maintaining operations.

5. Goodwill, Badwill, and Impairment

5.1 Goodwill

Goodwill is an intangible asset that arises in the context of a business acquisition or merger. It represents the additional value a buyer is willing to pay for a company beyond the fair value of its tangible and identifiable intangible net assets. This extra value is attributed to intangible factors not directly reflected in financial statements, such as brand reputation, customer loyalty, workforce quality, or business relationships.

Importance of Goodwill

- Reflects Strategic Value: Represents the value of the company beyond its tangible assets.

- Key in Acquisitions: Justifies significant differences between the purchase price and book value.

- Market Confidence: High goodwill can indicate a strong brand or a solid base of loyal customers.

How Goodwill is Calculated

Goodwill is calculated as the difference between the total purchase price of a company and the fair market value of its net assets (assets minus liabilities). In other words, it is the premium you pay for something. It is considered an asset (the premium itself) because the future value of the acquired asset is expected to increase.

Goodwill= Purchase Price − (Total Assets − Total Liabilities)

Example:

- Purchase Price: $1,500,000

- Identifiable Assets: $1,200,000

- Identifiable Liabilities: $300,000

Goodwill= 1,500,000 − (1,200,000−300,000) = 1,500,000 − 900,000 = 600,000

Characteristics of Goodwill

- Intangible: It is not a physical asset like buildings or machinery.

- Indivisible: Cannot be separated or sold independently of the company.

- Periodic Evaluation: Goodwill is not amortized but must be periodically assessed for potential value impairments.

5.2 Goodwill Impairment

Impairment occurs when the book value of goodwill exceeds its recoverable value, indicating a loss in its value. This impairment must be recorded as an expense on the income statement.

How to Calculate Goodwill Impairment (Example):

- Book Value of Goodwill: $500,000

- Recoverable Value of Goodwill: $400,000

- Impairment: 500,000 − 400,000 = 100,000

The company must record a $100,000 loss in its income statement and reduce the goodwill value on the balance sheet.

Reasons for Impairment

- Adverse market changes (competition, regulations, recessions).

- Loss of significant customers.

- Financial performance below expectations.

- Strategic decisions diminishing perceived company value.

Impact of Impairment

- Accounting: Reduces total asset value on the balance sheet and directly affects net income in the income statement.

- Financial: Can negatively influence investors' and creditors’ perceptions.

- Strategic: Reflects that the expected benefits of an acquisition or investment are not being realized.

Goodwill impairment ensures financial statements provide a more realistic view of a company’s intangible assets.

* Green flag: Goodwill less than 10% of total assets.

* Yellow flag: Goodwill greater than 50% of total assets (if goodwill impairment occurs, the stock would be severely penalized due to a significant loss in asset value).

6. Balancing the Balance Sheet

Balancing the balance sheet is a common accounting term referring to the process of ensuring that the accounts in the balance sheet are correctly recorded and meet the basic accounting equation:

ASSETS=LIABILITIES+EQUITY

When a balance sheet "balances," it means the total assets equal the sum of liabilities and equity, indicating that there are no arithmetic or recording errors in the main accounts. This balance is crucial as it reflects the relationship between the resources a company owns and the sources of those resources.

Steps to Balance the Balance Sheet:

- Verify Accounting Records: Review all general ledger accounts, ensuring that final balances are accurate and properly classified as assets, liabilities, or equity.

- Confirm Use of Double-Entry Accounting: In every accounting entry, the total debits must equal the total credits. If this condition is not met, discrepancies will appear in the balance sheet.

- Check Calculations: Ensure that the totals for the columns (assets, liabilities, and equity) are added up correctly.

- Corroborate Closing Accounts: Verify that temporary accounts (revenues and expenses) have been closed properly and their results transferred to equity.

Importance of Balancing the Balance Sheet:

- Financial Accuracy: A balanced sheet ensures that the financial statements accurately reflect the company's economic position.

- Regulatory Compliance: Prevents issues with external audits and legal regulations.

- Decision-Making: A reliable balance sheet is essential for financial planning and strategic decision-making.

7. Types of Debt

7.1 Loans: Direct financing provided by banks or financial institutions.

7.2 Lines of Credit: Revolving credit facilities

Revolving credit facilities are financial agreements between a company and a bank, allowing the company to access a credit limit as needed. The company can use, repay, and reuse the funds within the established limit.

Key Features:

· Revolving: As credit is repaid, the limit becomes available again.

· Interest on Used Amounts: Interest is charged only on the amount used, not the total limit.

· Flexibility: Ideal for covering short-term liquidity needs or unforeseen operational expenses.

Advantages for the Company:

· Quick access to financing without requiring additional loan applications.

· Helps manage cash flow and cover temporary deficits.

7.3 Bonds

Debt instruments issued by companies (or governments) to raise funds. When a company issues a bond, it borrows money from investors in exchange for periodic interest payments and repayment of the principal at maturity.

Key Features:

· Issuer: Can be a private company or a government entity.

· Interest Rate (Coupon): The percentage of interest paid periodically on the bond’s face value.

· Maturity Period: The time at which the issuer must repay the principal to investors.

· Face Value: The bond’s nominal value, which is repaid at maturity.

· Purpose: Companies issue bonds to finance projects, expand operations, or address liquidity needs.

Advantages for Investors:

· Provides regular income through interest payments.

· Less risky than stocks, as bondholders have priority over shareholders in case of bankruptcy.

Example:

A company issues a 5-year bond with a face value of $1,000 and a 5% coupon. Investors receive $50 annually per bond and, at the end of 5 years, recover their initial investment.

7.4 Convertible Bonds

Hybrid instruments between debt and equity. Initially, these function like traditional bonds that pay interest, but investors have the option to convert them into company shares at a predetermined price.

Key Features:

· Conversion to Shares: Investors can exchange the bonds for a fixed number of shares during a specific period.

· Lower Interest Rate: Offers a lower coupon compared to traditional bonds due to the added benefit of conversion.

· Flexibility: If stock prices rise, investors can convert the bonds into shares to realize capital gains.

Advantages for the Company:

· Attracts investors interested in potential capital gains.

· Delays issuing shares, avoiding immediate equity dilution.

Example:

A company issues convertible bonds with a $1,000 face value, a 3% coupon, and a conversion price of $50 per share. If the stock price rises to $60, investors can convert the bond into shares, gaining additional profit.

7.5 Contingent Convertible Bonds (CoCo Bonds)

A special type of hybrid bond primarily issued by financial institutions.

Key Features of CoCo Bonds:

-

- Contingent Conversion: These bonds convert into ordinary shares of the issuing company when a specific "trigger" event occurs, such as the capital ratio falling below a regulatory threshold (e.g., a minimum solvency level).

- Loss Absorption: Instead of converting into shares, some CoCo bonds simply reduce their face value, meaning investors bear partial or total losses.

- High Yields: These bonds offer higher interest rates than traditional bonds due to their increased risk.

- No Fixed Maturity (Perpetual): While some have a maturity date, many CoCo bonds are perpetual, meaning there is no set date for principal repayment.

- Issued Primarily by Banks: Popular in the financial sector, they help banks meet capital requirements under international regulations like Basel III.

Uses of CoCo Bonds:

-

- Strengthening Regulatory Capital: Designed to act as a cushion during financial stress, helping banks meet capital requirements without issuing shares under adverse conditions.

- Avoiding Government Bailouts: Serve as a tool to absorb losses internally (bail-in) and reduce dependency on government assistance (bail-out).

Practical Example:

A bank issues a CoCo bond with a $1,000 face value and a 7% coupon. If the bank’s capital ratio falls below 7% (the minimum set by the regulator), the bond automatically converts into shares or loses part of its face value, as stipulated in the contract.

8. Types of Shares

8.1 Common Shares (Ordinary Shares):

- Represent ownership in the company.

- Provide voting rights in shareholder decisions (e.g., electing the board of directors).

- Allow participation in the company's profits through dividends, if approved by the board.

- Their value can fluctuate based on the company’s performance and market conditions.

8.2 Preferred Shares:

- Typically do not grant voting rights.

- Have priority over common shares in dividend payments.

- In case of company liquidation, preferred shareholders are prioritized for recovering their investment before common shareholders.

- Dividends are usually fixed.